"TFW NO GF" Is the Defining Documentary of a Generation

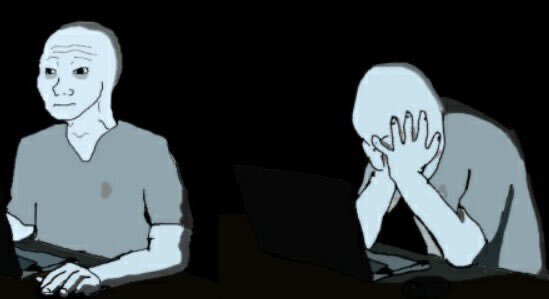

TFW NO GF is a movie named after a meme. The new documentary, now available on Amazon Prime and YouTube, begins with ‘Wojak’—the grey, anguished avatar of the online underworld—and his favorite caption, “TFW NO GF”: “that feel when no girlfriend.”

But TFW NO GF isn’t just a documentary on Wojak, or the r9k board on 4chan that he inhabits; it isn’t an ‘incel movie,’ although it examines them; and it isn’t only about young, alienated men. It covers the gloom of an entire generation—a disaffection overlooked yet fanned by the hysteric social movements of the 2010s. TFW NO GF is the mainstream’s first hard look at this phenomenon, and for that reason, there is no more important documentary to watch today.

At the heart of TFW NO GF are the stories of four young men: Sean, Kyle, Charels, and Kantbot. At first, all we see is their misery—they are NEETs (not in education, employment, or training), with no future and few friends. As the film unravels, we realize that each character has been chosen for his online notoriety: Kyle made a video about the blackpill, the ideology that there is “no hope” for incels; Charels’ bitter tweets turned him into a media scapegoat as a ‘misogynistic jihadi’; Kantbot bizarrely related Donald Trump election to the raising of Atlantis in an interview.

What binds these characters is the hell that the mainstream media raised about them. Yet, as TFW NO GF shows, the juxtaposition between its subjects’ media portrayals and their corporeal forms is jarring. In reality, these men (with the exception of the impressive Kantbot) are lost, rabbit-eyed souls, drifting alone through the American wasteland, their only anchor the forums, image boards, and MMORPGS (online role-playing games) where they can commiserate with other men.

In a different era, these men might have been saved. Someone would hear about a friend’s younger brother playing video games all day, or a mother’s son who just wouldn’t leave his room. “Hey, why don’t you come down to the men’s club at the VFW. We meet Wednesday night. Chance to blow off some steam and talk about life.” “Me and the guys go out shooting every week—why don’t you come with us next time? Sure beats sitting around all day.” Gradually, a hikikomori would be eased out of his misery—he would be set up a with a job, a date, a reason to live.

In postmodern culture, there seems to be no desire to see such men climb out of their holes. Attending college in the first half of this decade, I noticed a peculiar, even evil satisfaction in the suffering of such young white men as getting their “just desserts.” Any complaint was a symptom of poisonous entitlement. It was their burden to simultaneously accept their privilege, their predicament, and their pain.

Just as perverse is the strange stigmatization of men’s self-improvement. In the last decade, whenever a men’s movement emerged that promoted some type of discipline or development, the mainstream media lunged over each other to see who could tie it to the alt-right (i.e. this ridiculous Rolling Stone article about NoFap or this Mel Magazine article about raw eggs). Jordan Peterson, whose primary message to young men is to “clean your room and sort yourself out,” is demonized as a Nazi by a whole swath of society, and his majority-male audience has been used as a line of attack against him, as if no one should be trying to target and help young men.

The males of TFW NO GF, while not all able to articulate as clearly as Kantbot, feel this demoralizing culture. “No one cares about you if you’re a guy,” says Charels. That’s not necessarily true; there are a few men that everyone cares about—who keep the gate and make the money and hold the power—and it is these ‘Chads’ (as incels call them) who run the world and get #MeToo’d.

Infinite more men are total nobodies. Their only recourse is to scrawl a message in a bottle and throw it into the digital abyss—“TFW NO GF.”

When I was young and watching the subversive “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart” with my dad, it was clear who was right and who was wrong. The bad ones were those who hated fun—the Puritans who sought to ban violent video games, punk rock, and gangsta rap. We kids swore to never be like those adults. But somehow the kids grew up to be millennials who filled the ranks of Vox, Buzzfeed, and Huffington Post, and became the finger-waggers themselves—the ones who shamed teenage fans of XXXTentacion, who misinterpreted trolly memes as Nazism like their predecessors did with Satanism, who transformed art and culture and comedy into a moralist circus.

In contrast, even though Wojak is the avatar of melancholy, TFW NO GF shows the endlessly inventive ways he’s been memed: in car, in cubicle, in battle, in space. In a society traumatized by cancel culture, where everyone bites their lips in fear of offending, memes were one of the last funny things. In fact, in TFW NO GF, “The Daily Show” is used as the epitome of lameness—when a mom-blogger suggests that kids who spend too much time on 4chan should watch the show with their parents and write an essay on why it's hilarious, Charels remarks “I can’t imagine anything more uncool.”

TFW NO GF contrasts the mirth of memes—for these guys, maybe the only thing that makes them smile— with how laughably out-of-touch the media is with the needs of young men: “21 Reasons Why Being a Cuck Isn’t a Bad Thing,” one Buzzfeed article shown says. The indignance of Kyle that incels are seen as an organized terrorist group, or the exasperation of Charels when asked if he would ever do violence against women, are shown alongside New Yorker and Huffington Post articles on why we should fear men like Kyle and Charels.

The elusive Kantbot. Source: “TFW NO GF”

Every monopoly is eventually toppled. Gradually, individuals took ice picks to the orthodoxy—Kanye West and Dave Chappelle and Anna Khachiyan and Azealia Banks and Mike Crumplar and Arielle Scarcella and Kantbot all had exciting, heterodox, controversial views, that showed they were willing to wade into the toxic sludge and pan for gold. Khachiyan even interviewed Kantbot this week. They all paid a price: Khachiyan’s podcast has been called a “nazi barbie” podcast, Dave Chappelle is named a bigot, Arielle Scarcella has been demonetized, Kanye West has been cancelled, Kantbot has been doxxed. But, like the heroes of every generation, they made it okay to be yourself.

TFW NO GF, on its own, doesn’t make any overt political statement. The director’s revolutionary act is simply to find the humanity in these radioactive characters. Any other documentarian could have gone for a far easier take: a montage of Charels shooting semi-automatic weapons, a close-up of Kyle’s Confederate flag lapel pin, and Kantbot’s messianic interpretation of Donald Trump would have been framed to confirm the ‘woke’ assumption that we live in a country a 4chan activation away from hordes of men shooting up SoulCycle.

Alex Lee Moyer does what countless other journalists and documentarians failed to do—she humanizes the Other. The identity of TFW NO GF’s director—Moyer is a young, attractive woman—makes the movie all the more incredible.

In the long term, I’m not sure what the media will make of TFW NO GF. Perhaps they’ll realize that many of the ‘boogeymen’ they had been demonizing over the last decade were simply lanky, flabby, wry trolls—ironically, some of the most harmless men in society.

More predictably—and because many of their own articles were shown in the film—there will be a backlash against the documentary’s failure to recognize the “homophobia, racism, transphobia, sexism, misogyny, and white supremacy” that undergirds these losers’ worldviews. There is genuine wickedness on these forums, but the rush to categorize everything deviant as ‘alt-right,’ and the utter humorlessness with which they’ve interrogated meme culture, has been an abject failure of mass communications. That a single documentary could shatter their narrative is existentially threatening.

But the documentary will reach the people. Many of them will not be young men, but those who identify with their isolation, alienation, and malaise. We’ve all felt the degradation of postmodernity—the dystopian self-policing, the repressive consensuses, the eternal suck of the screen, the atheism and nihilism and fatalism that wants us to lie down and die. Many of us had girlfriends and boyfriends, but we still understand “TFW NO GF.”

The ‘TFW NO GF’ phrase was first posted on 4chan in 2011. For many, it would come to define the disillusionment of the 2010s. But the documentary ends with an important message for the 2020s.

After several years, the film finds the men all doing better: Sean has begun competitively weightlifting and reading voraciously, Charels has found a girlfriend, KantBot is supporting himself with his philosophical content. Having lost faith in larger forces to help them, they’ve begun to make their own way—“to create their own reality,” as Kantbot says, like Elphaba in Wicked, even if society continues to shame them.

I previously held that the defining documentary of our generation was Weiner, but TFW NO GF is right up there with it. Plenty of mainstream documentaries have been made about those left behind economically, but none have covered those left behind culturally. Yet TFW NO GF also spotlights the rich repository of culture that was continuously created with Wojak. All along, even in the darkest dark, people found ways to cope—sometimes destructively, sometimes transgressively, sometimes beautifully.

The spell is broken. The long decade is over. There is hope for the broken-hearted.

Follow Zachary Emmanuel on Twitter.