The Secrets of Lake Mega-Chad

The Sahara was once green and filled with life. What mysteries lie buried under its sands?

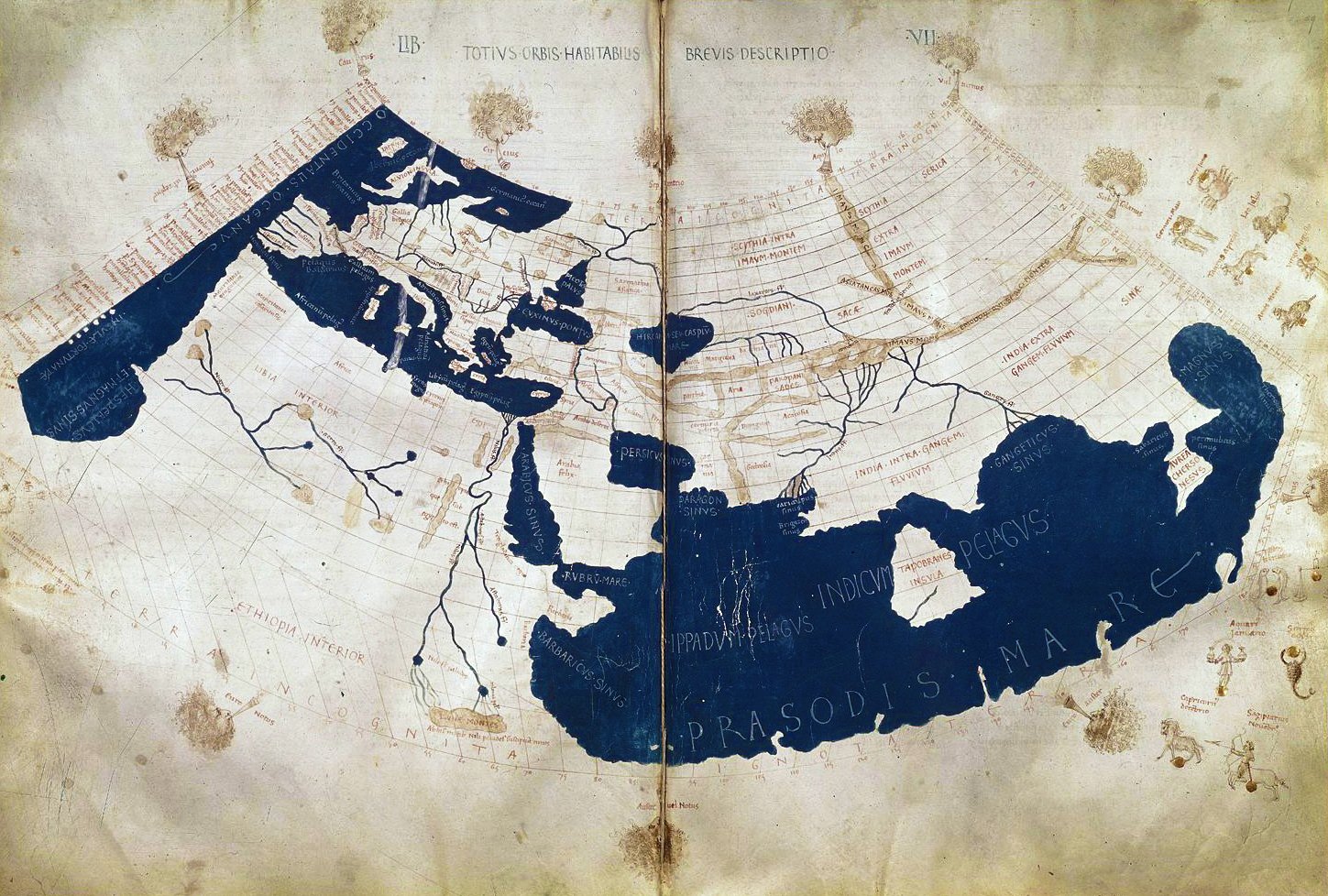

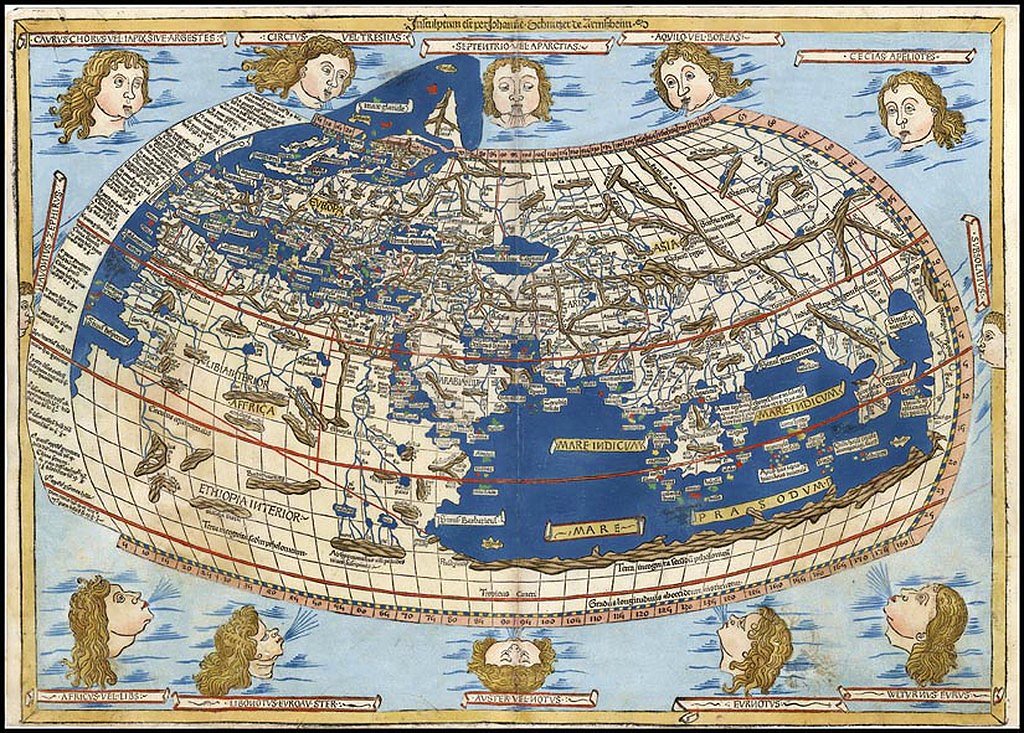

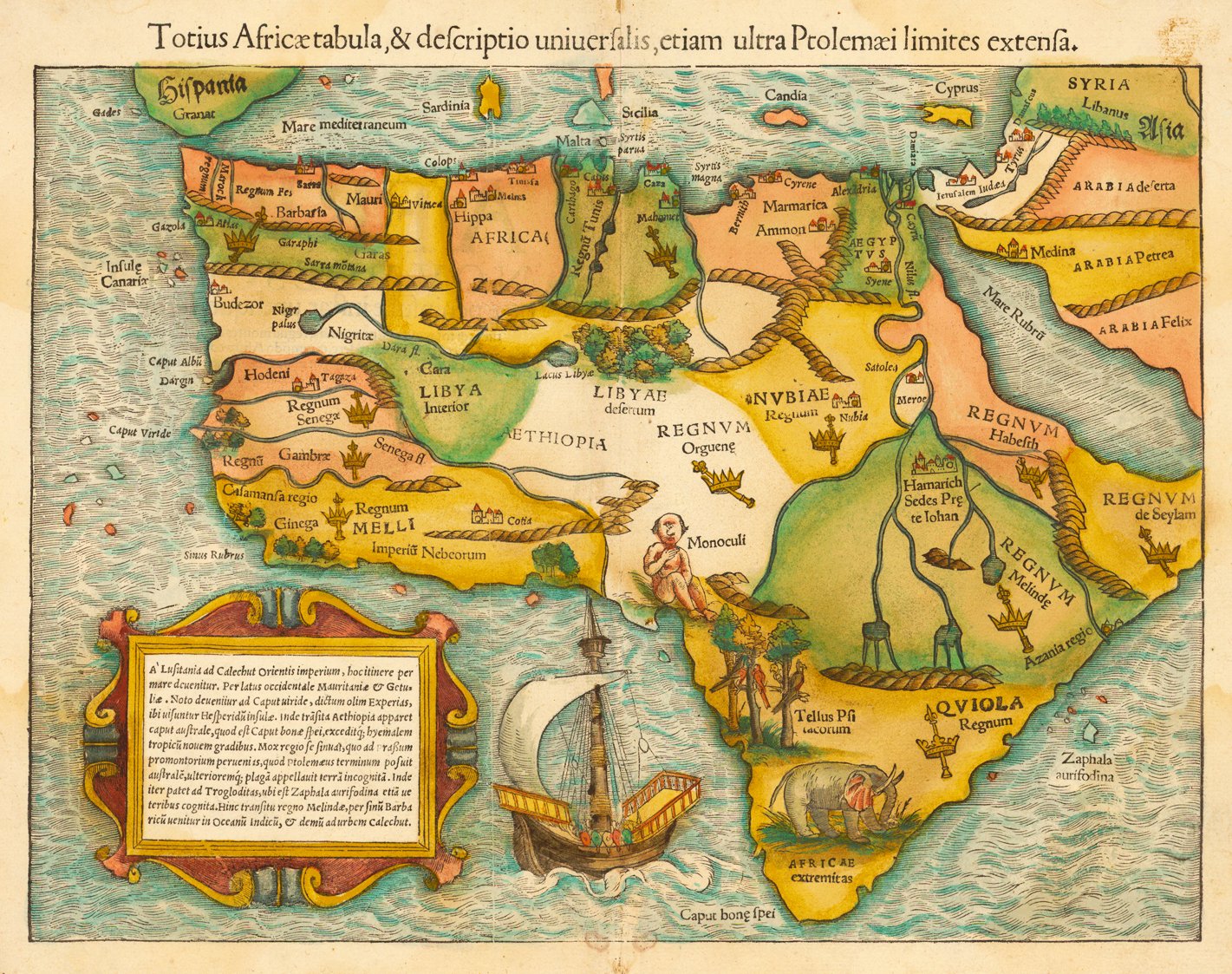

Ancient maps have a strange way of depicting Africa. In maps created from 2nd-century Roman projections, Northern Africa is shown teeming with rivers and lakes. In the Kangnido, a Korean world map created in 1402, a gigantic lake occupies the center of Africa. The Sebastien Munster map from 1554, one of the first attempts at mapping the totality of the continent, seems to hallucinate a lush forest in the Sahara desert—today one of the hottest, driest, and most inhospitable regions on the planet Earth.

While it may be tempting to dismiss such details as the doodles of a kooky cartographer, these maps were often the result of decades of painstaking work, centuries-old expeditions, and knowledge acquired over millennia. East Asia’s Kangnido map presciently traced the southern tip of Africa before Europeans had ever circumnavigated its shores. And in fact, a series of rivers and giant lakes once did exist in Africa: massive paleo-lakes with names like Lake Fezzan, Lake Turkana, Lake Chotts, and their king, which would be the largest lake on Earth today, Lake Mega-Chad.

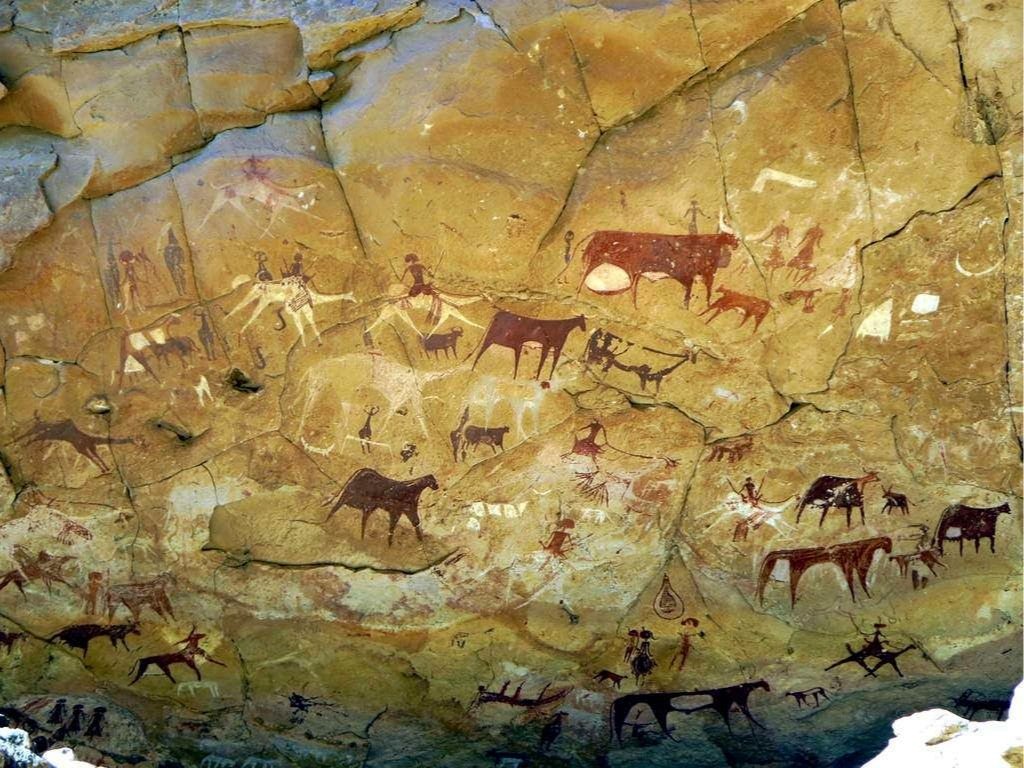

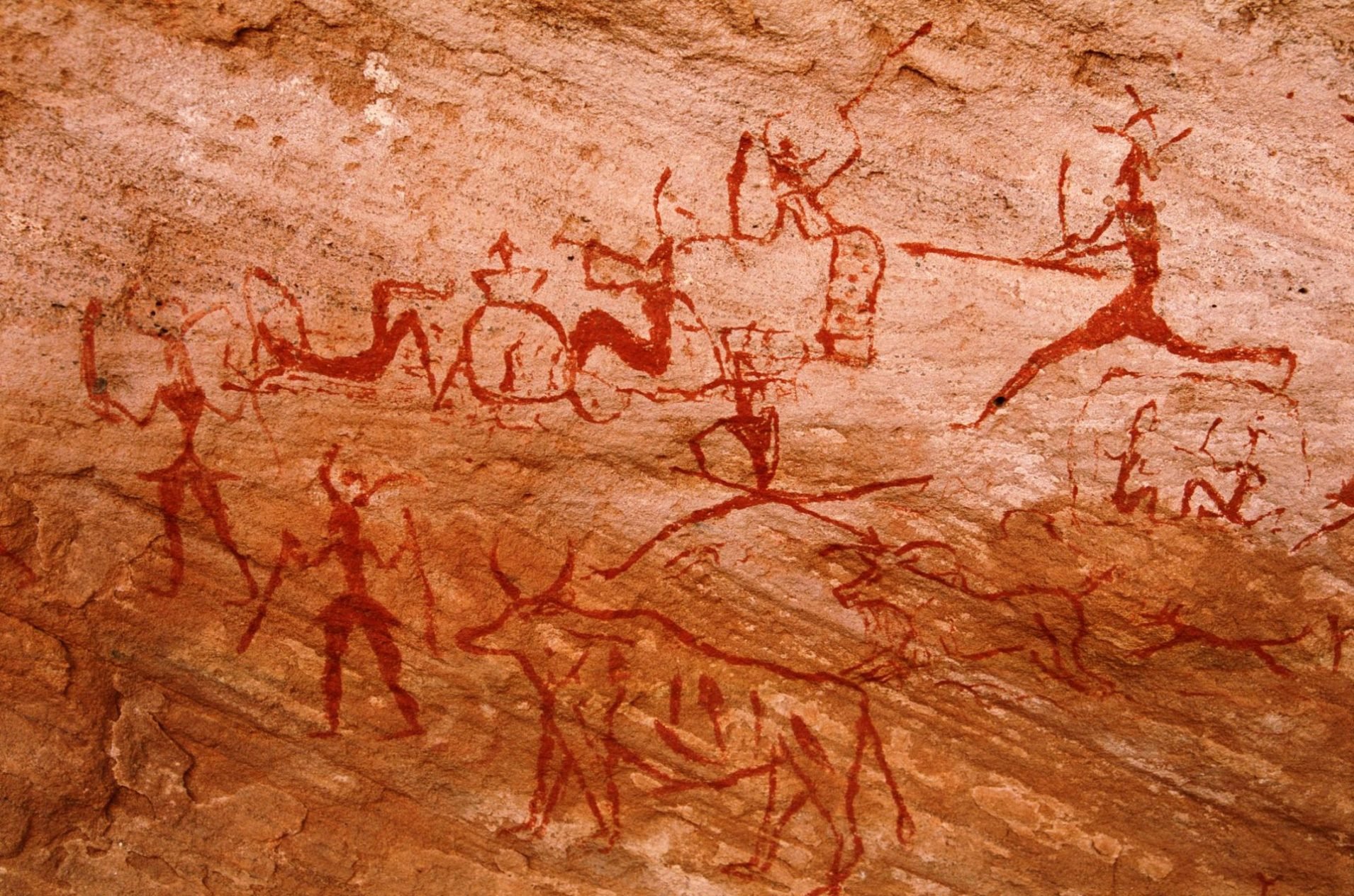

Prehistoric paintings from the Cave of the Swimmers.

Lake Mega-Chad’s meme-worthy name alludes to its power—only a Lake Giga-Chad could rival its name physiognomy—but this lake, and the forces behind it, may have played a bigger role in human history than previously understood. Investigating its mysteries could help explain everything from the watery anomalies on early maps of Africa, to the source of power for both an ancient desert civilization and the Amazon rainforest, to the locations of the City of Atlantis and the birthplace of Biblical Noah. The same region we call the Sahara desert was once lush and alive—and this may have been the norm for most of human history, not the exception. The sands of today bury the secrets of the dead…

Up to around 3000 BC, Lake Mega-Chad measured over 150,000 square miles wide—just bigger than the Caspian Sea, the world’s current biggest lake. Lake Mega-Chad flexed its physique on a North Africa that would be unrecognizable today: a vast, verdant, and highly populated grassland nourished by rich rivers and mammoth lakes. Humans thrived here, creating arguably the world’s largest outdoor art museum in the form of hundreds of thousands of rock art paintings of animals who flourished in this vanished ecosystem. The Cave of the Swimmers, located in the Libyan Desert region of the Sahara, has 9,000-year-old paintings of water-dwelling hippopotamuses, giraffes, and humans who appear to be swimming. Nigeria’s Dufuna canoe, dated to around 8,000 years ago, is the second-oldest known boat in the world; found underground by a herdsman digging a well, it most likely sailed the now-vanished waters of Lake Mega-Chad.

At one point, Lake Mega-Chad began to recede. The pace at which it did so is a matter of debate; we do know that its decline started roughly 5,000 years ago, but that that it was still a huge “lake of hippopotamus and rhinoceros” when a Roman expedition reached it in the first century AD, returning with a two-horned rhinoceros that actually fought and killed in the Coliseum. The lake’s disappearance over the last fifty years, however, has been precipitous. Since the 60s, Lake Chad has shrunk by over 90% in both surface area and volume—a decline, coincidentally, corresponding to the drop in men’s testosterone levels and the quality of manufactured goods. It now measures barely 500 square miles across, around .003% of its prehistoric size.

Even its diminished state, Lake Mega-Chad has exerted enormous influence over world affairs. Its northern Bodélé basin has become the single greatest dust source on the planet. Transatlantic winds lash the Amazon with Mega-Chad’s remains; this dust is one of the primary fertilizers for the world’s biggest rainforest. The receding lake also left water trapped in aquifers: 30 billion gallons of “fossil water” from Lake Chad and other paleolakes were estimated to have been mined by the Garamantes, a mysterious desert civilization that endured from roughly 500 BC to 700 AD.

From space, one can see massive Saharan dust storms traveling to South America.

Before continuing, it’s important to understand why Lake Mega-Chad disappeared. Lake Chad didn’t transition because of human-induced climate change or glacial cycles, but due to esoteric Milankovitch cycles, which describe how Earth’s movements through space affect its climate. 10,000 years ago, a slight wobble in Earth’s rotational axis (imagine the invisible circle drawn by the tip of a spinning top) meant that Northern Africa received 7% more solar radiation. This triggered a domino effect which led to at least 50% more annual precipitation over North Africa. Water was abundant. Forests and grasslands bloomed. The Sahara became a savanna.

This may seem counter-intuitive: hotter temperatures equal a greener Sahara? Yet in North Africa, high temperatures on land will trigger a massive air exchange with the Atlantic, and for a season, the normal “trade winds”—which carry dust out Africa and across the Atlantic—will reverse. This event is called the West African Monsoon, where water from the Atlantic rushes in and rains over the Sahara. And what’s there to capture the increased rainfall? The basins and depressions that once held the ancient paleo-lakes.

A visualization of the Sahara during the African humid period.

The last time the Sahara was green is named the African humid period, which is believed to have started around 15,000 years ago and ended around 5,000 years ago. That was just the latest of hundreds of similar cycles dating back millions of years. 10,000, 50,000, 120,000 years ago and beyond, wetter conditions in the Sahara allowed humans to cross Africa and migrate into other continents.

This tightening of Africa’s belt—cleaving with an inhospitable desert the north and south of the continent—is connected to monumental events in human history, including the the sapiens-Neanderthal split and the legendary “trek out of Africa.” It is also associated with the rise of Ancient Egypt, as populations clustered around the Nile as the savannah withered. The giant lakes and green Sahara became harder and harder to remember until they moved from memory into myth: the ancient Greeks spoke of their sun god Helios’ son, Phaethon, who lost control of his father’s sun-chariot in an impetuous bid, setting the world on fire, scorching the grasslands of Africa into desert.

Speculated changes in the Sahara over the last 5,000 years ago. Deep greens are forests, lighter greens are farmlands & savannas, yellows are grasslands, and oranges & browns are desert.

Yet rumors of Mega-Chad’s death may have been greatly exaggerated; a greener Sahara may have endured longer than we thought. Researchers from the University of London recently found that Lake Chad has exhibited a “nonlinear response” even to Milankovitch cycles over the last 5,000 years, with its Bodélé Basin drying out only 1,000 years ago. A moist era in North Africa re-occurred between 500 BC and 300 AD which directly corresponds with the rise and reign of Garamantian civilization. While we still don’t know much about these sand-people, they were described by Herodotus as a “very great nation” who rode chariots and lived among “many fruit-bearing palms.” Analysis of Garamantian skeletons suggests their males lacked exceptional upper body strength, indicating that even up to the Classical period, “life in the Sahara did not require particularly strenuous daily activities.”

The idea of the desert Sahara as a fixed, unchanging environment in human history must be demolished. In fact, the Sahara has had a continuous record of human inhabitation interrupted by dry spells: from the giantlike Kiffians who lived in the area from around 10000 to 6000 BC, whose skeletons measure 6 feet 6 inches tall; to the shorter Tenerians who spread out over the region from around 5000 BC to 2500 BC, whose hardened musculature suggests a fishing-based culture; and more recently, the Kanem-Bornu Empire, who controlled the area around Lake Chad and lasted from 700-1900 AD, and which was considered by 14th-century historian Ibn Khaldun to be on par with the “Romans, Turks, Chinese, and other great civilizations.”

All sorts of interesting things happen when we consider the Sahara as a place of history and the possible origin of myth. Jimmy Corsetti appeared on the Joe Rogan podcast to explain the increasingly popular theory that the Richat Structure, located in modern-day Mauritania, is the lost city of Atlantis. Its geological features eerily mirror Plato’s description of Atlantis: an island surrounded by three rings of water and two of land, almost exactly 23 kilometers across, with mountains to the north and an ancient ocean to the south. Interestingly, Plato learned about Atlantis from Solon, who learned about it from the Egyptians—the descendants of those who migrated over the drying Sahara into the Nile region.

Side-by-side comparison of the Richat Structure, located in modern-day Mauritania, and an artist’s rendering of Atlantis.

Dissident academics have also claimed Noah was born in the Lake Chad region between 4000-3200 BC, this being “the only place on Earth that the natives call Noah’s homeland—Bornu meaning ‘land of Noah.’” British anthropologist Sir Walter Keith argued the Sahara itself was the mythical Garden of Eden, with man driven away not by a flaming sword but by “a flaming sun.”

Knowing this, it’s not so crazy to attribute the apparent anomalies on old world maps to folk memories of Lake Mega-Chad, other ancient lakes and rivers in Africa, and a greener Sahara. Maps from antiquity match up remarkably well to outlines of the ancient paleo-lakes and rivers that flowed across the Sahara in times immemorial—and, now we know, in times more recent. If Australian Aboriginals can preserve memories of coastlines from 10,000 years ago through oral tradition, it’s unsurprising that a Lake Mega-Chad that began shrinking in 3000 BC would show up in a medieval Korean world map, or that forests would be drawn onto Africa well until the Age of Exploration.

Those with a linear view of history are doomed to repeat the past. The Sahara is merely a liminal space: in-between habitation; resting, not dead. In our time, there is an unlikely force working to restore the Sahara and revitalize Lake Chad: human-induced climate change. Yes, higher temperatures on land will invite more rainfall to the continent. In fact, human-induced climate change is predicted to lead to vegetation covering at least 45% of the Sahara in the future. And more recent analyses of Lake Chad have found that in the last decade, it has in fact stopped shrinking and is currently experiencing increased rainfall.

Aided by ambitious geo-engineering projects such as the Great Green Wall Initiative as well as the noxious fumes of our civilization, Lake Mega-Chad plots a return to the course of human history. It is not a question of “if,” it is a question of “when.” Given the abrupt nature of its previous comings and goings, Lake Mega-Chad may return sooner than you think. With it will arrive new possibilities, a new world, and, as they say, the return of very old friends…

Follow Countere Magazine on Twitter.

Other Articles You May Enjoy

She Practiced Santeria: A Tale of Demonic Seduction